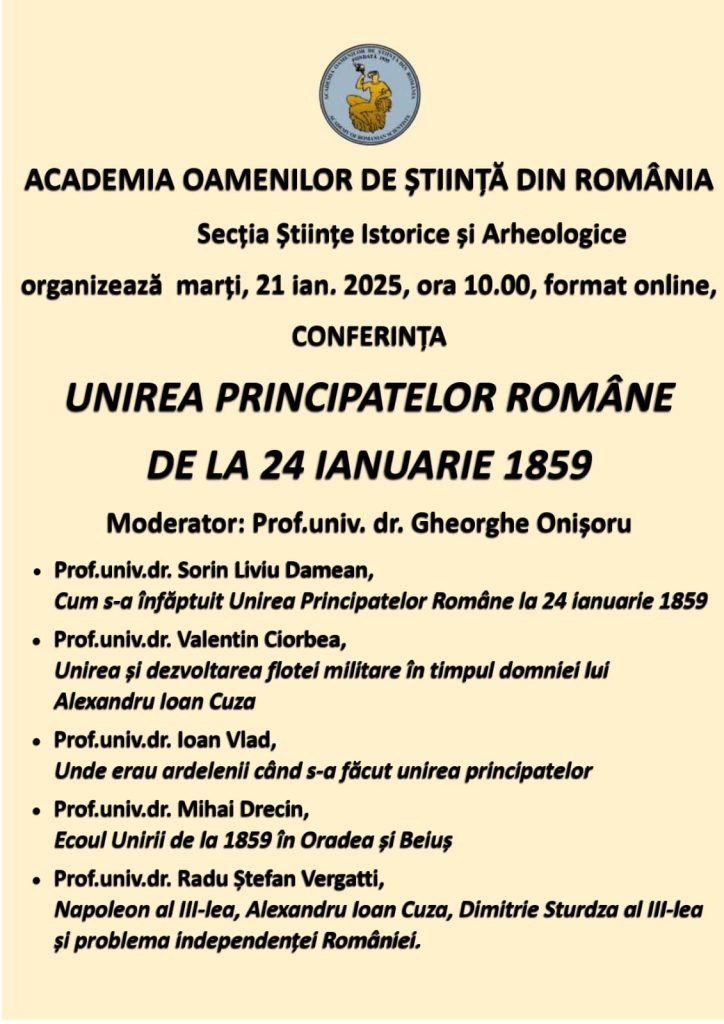

THE ACADEMY OF SCIENTISTS OF ROMANIA, Section of Historical and Archaeological Sciences, organized on 21 January 2025 the online conference The Union of the Romanian Principalities of 24 January 1859.

The conference was opened by Prof. Dr. Doina Banciu, President of AOSR and was moderated by Prof. Dr. Gheorghe Onișoru.

Prof. Dr. Sorin Liviu Damean gave a speech “How the Union of the Romanian Principalities was accomplished on January 24, 1859”.

According to him, the double election of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as Prince of the United Principalities in Moldavia and Wallachia was not a spontaneous act. It was prepared for a long time. Since the beginning of the 19th century, we have been witnessing the spread of the principle of nationalities and, in this context, the movement of national awakening of the Romanians, which began in 1821 with Tudor Vladimirescu, who tried to work with the Moldavian boyars to regain the old privileges of the two principalities. We can speak of an identical status, they were under Ottoman suzerainty, so the moment of 1821 was the impetus towards the national idea of establishing a national state in favorable circumstances.

The desired result was not achieved either diplomatically or through memorials and reform proposals addressed either to the suzerainty or, from 1899 onwards, to the Protectorate, i.e. Tsarist Russia. Therefore, a favorable moment was awaited on the external front, and this was to come in 1848, when the Spring of the Peoples took place, when the French revolution was the signal for all the other revolutions on the European continent. At that time, the Moldovan and Montenegrin patriots studying in Paris thought that the external context had been created for them to obtain rights, greater autonomy and, if possible, even independence. What matters is that we find the idea of national unity in two documents.

One of them is the pact or the agreement signed by the Moldovan patriots who took part in the Blaj Assembly of May 3-5, 1848 and who arrived in Brasov on May 14, 1848, and drafted the document Our Princes for the reform of the homeland, which states that the union of Moldavia and Wallachia into a single unchanged state is one of the Romanians’ wishes.

The idea was to be taken up again later, in August 1848, by Mihail Kogălniceanu, in the well-known programmatic document. He was then in exile in Bucovina, where he spoke of the wishes of the National Party in Moldova, saying so beautifully that the union of Moldavia and Wallachia into a single state was, in fact, the keystone without which the entire national edifice would collapse. It was not possible to unite Moldova and Wallachia into a single state in 1848, given the role played by Tsarist Russia in defeating any revolutionary unrest. The Pașoptists, those who had taken part in the 1848 Revolution, would go into exile, but in exile they would support the cause of national unity, both in the European press and through their personal representations in the main European capitals. This is perhaps one of the most intense periods of the exiles since 1848, when they try to demonstrate to Europe that we are a people of Latin descent, of the same origin, speaking the same language, with the same customs and beliefs, and in order to gain the support of European public opinion, the idea of establishing a nation state here at the mouth of the Danube, which would in fact be a buffer state against Russian expansion, was undoubtedly also launched. The goals of Tsarist Russia were known to all, namely to dominate the Balkan Peninsula, to reach Constantinople, to seize the straits and, eventually, the Mediterranean. In other words, Tsarist Russia aimed to become an heir to the former Byzantine Empire, starting also from the Orthodox faith, hence the Orthodox messianism of Tsarist Russia.

Such an objective, of course, was not one that would be accepted by France in Napoleon III’s palace or by Great Britain with Queen Victoria, a country that controlled the Mediterranean Sea at the time, which provided the trade route to the Indies, and which was not interested in Russia’s control of the two straits of the Black Sea and, equally, of the Mediterranean.

Of course, the revolutionaries from the Mountains remained in exile for a long time, even after a new Russo-Ottoman conflict broke out, which was known as the Crimean War. It is less well known that the Montanists, under the leadership of Gheorghe Magheru, the former revolutionary of 1848, even tried to form a legion to participate alongside the Ottoman Empire against Tsarist Russia.

The question arises, why this involvement together with the Ottoman Empire against Tsarist Russia and it was clear that the reason was the Russian protectorate, a protectorate whose instrument were the two organic regulations of 1831 and 1832, almost identical in content, which eventually helped to chart the path of modernization, but which clearly specified in the additional article of 1837, that no change in domestic legislation could be made only with the support of the Suzerain Court and the Protectorate Court, which means a serious violation of autonomy. This involvement of a Romanian legion in the Crimean War was not possible. The Ottoman Empire refused to accept such participation.

However, the Romanians realized that the outbreak of war could be a favorable moment to support their cause when, miraculously, France and Great Britain joined the Ottoman Empire on the same side, so that Russia, the combatant, would be isolated. What is more, Austria or the Habsburg Empire, which would take over the administration of the Principalities from the end of 1854 with its own troops, would intervene to replace the Russian troops and of course to try to establish a favorable trend in the Principalities.

The fact is that the defeat of Tsarist Russia was looming as early as 1855, armistice negotiations were launched and a conference was convened in Vienna in March 1855, where the conditions that the European powers would impose on Tsarist Russia were to be discussed.

It is interesting that at this conference, the representative of France will make a surprising proposal for many of the participants, that the two principalities that had been occupied by Tsarist Russia at the outbreak of the Crimean War, should remain under Ottoman suzerainty, but that the Russian protectorate should be removed and replaced by a collective European guarantee. Moreover, the representative of France puts on the agenda the issue of the Union of the two principalities, Moldova and Wallachia, into a single state under a foreign prince.

The idea, naturally, did not meet with the agreement of the European powers. Most vehemently opposed to such an idea were, of course, the Ottoman Empire and, equally, the Habsburg Empire. The Ottoman Empire feared that in this way the two united principalities with a foreign prince would mean the break away of the principalities from Ottoman suzerainty and that such a model could also be adopted by the other Balkan peoples still under Ottoman rule.

Prof.univ.dr. Radu Ștefan Vergatti – Napoleon III, Alexandru Ioan Cuza, Dimitrie Sturdza III and the problem of Romania’s independence.

The Emperor of Russia, Tsar Nicholas, considering himself an absolute autocrat – especially after in 1848 – 1849, with the help of Marshal Ivan Fyodorovich Paskevich, he managed to quell the 1848 – 1849 Revolution in the Habsburg Empire and then to become a kind of “gendarme of Europe” – considered himself entitled to fulfill the wishes of his ancestors. He wanted to conquer the city of Constantinople and to this end he organized a series of extremely persistent, even violent, diplomatic actions and used Alexander Sergeyevich Menșikov to carry out his plan. The tsar was sent to Constantinople as plenipotentiary ambassador of St. Petersburg.

He presented Sultan Abdul-Medjid with a request that had already been fulfilled, but which could not succeed: he asked that the Tsar, as protector of all Orthodox in the world, be given possession of the church in Bethlehem, where Jesus Christ was supposed to have been born.

The request was refused. As a result, on October 4/16, 1853, war broke out between the Tsarist Empire and the Sublime Porte. As a result, on March 27, 1854, France entered the battle alongside the High Porte.

It immediately joined France, England, the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of the Two Sardines.

From there it went on to take the fighting to the Crimean Peninsula, a sad realization for the Russians because they had defeat after defeat.

On March 2, 1855, Tsar Nicholas I died. He was succeeded by his son, Alexander II, who capitulated, leading to the peace conference of February-March 1856 in Paris.

There, during the discussion, among other issues, the question of the Danubian principalities was raised, an issue that was supported with particular ardor by Count Alexandre Walewski, the French Foreign Minister, and Count Pavel Kiselyov, who was the Russian Ambassador in Paris.

The problem of the Danubian principalities was presented by Gheorghe Magheru, a handsome man, a good French speaker and especially well liked in the Parisian salons. He was successful. The issue was formulated in such a way in the acts of the Congress that on January 5 and 24, 1859, Alexandru Ioan Cuza could be elected as prince in Iasi and Bucharest. In this way a personal union was achieved through him, but it went further. With the support of Napoleon III, on February 25, 1856, Alecsandri and a French diplomat met secretly in Italy.

The two diplomats, representatives of the Romanians and the French, in fact of Alexandru Ioan Cuza and Napoleon III, discussed the situation in South-Eastern Europe and it was requested that Alexandru Ioan Cuza support the intervention of the French army in the fight against the Habsburg Empire and, in return, Napoleon III helped to support the option of independence for the Romanians. It was the second step after the Union, the independence in the progress of the Danube principalities, named in 1860, in official documents, Romania.

In 1860, Emperor Napoleon III wrote a secret letter, absolutely secret, to Alexandru Ioan Cuza, in which he asked and suggested to Alexandru Ioan Cuza to recruit a number of soldiers and to increase the Romanian army to 20,000 men.

The Emperor also wrote to Alexandru Ioan Cuza to use the 20,000 men to make a demonstration on the Romanian bank of the Danube, because the river was then considered the border between Romania and the Sublima Poarta. This demonstration could have been a parade, a military exercise to show that Romania had an impressive military force with which it could act.

Unfortunately, this letter was found on the ruler’s desk by the young Dimitrie Sturdza Miclăușanu, a cousin by marriage to the ruler. This Dimitrie Sturdza, who spoke German well, was the king’s secretary and had the task of informing the ruler of everything that was being written in German newspapers and magazines and, if necessary, to reply. However, although he was well liked by the ruler (who, being 14 years his senior, considered him a kind of son and called him Mitiță), he took the letter and delivered it to the consuls of England, Russia and Austria, who were against the Romanian uprising.

In England, the letter was immediately published, Napoleon III found out about it and wrote a telegram to Alexandru Ioan Cuza, in which he told him that a country with such traitors does not deserve independence. Alexandru Ioan Ioan Cuza lost his calm and love for Dimitrie Sturdza, slapped and shoved him on the palace staircase and threw him out. Dimitrie Sturdza had done great harm to Romania at the time, because he had stopped Romania from gaining independence diplomatically. It was an act of high treason.

The young man, described by Sabina Cantacuzino as a small man, with a crooked face due to a stroke (stroke), with a shrunken eye, ran in a hurry to the stables of his palace and, because he was a good horseman, he mounted and fled to Giurgiu, from here, in the Sublima Poarta, he settled in Istanbul and by unknown means he got in touch with the opponents of Alexandru Ioan Cuza and they formed that monstrous coalition. They maneuvered from home and abroad for the overthrow of Alexandru Ioan Cuza, who on the night of February 10-11, 1866, was forced to abdicate.

Dimitrie Sturdza participated in this forcing of the ruler Alexandru Ioan Cuza to abdicate, broke into the palace and took all the royal archives in the palace in Bucharest, so that the state was later only the Archives of Ruginoasa.

This archive of Alexandru Ioan Cuza will be kept by Dimitrie Sturdza until 1912, when it will be given to Ion Bianu, director of the Academy Library, but it will only be seen in 1929, after the death of Ionel Brătianu, son of Ion Brătianu, one of the conspirators who led to the abdication of Alexandru Ioan Cuza. It is confirmed by documents, by the testimony of Colonel Lipan, of Theodor Rosetti, the brother of Mrs. Elena Cuza, and by the testimony of Mrs. Elena Cuza, the betrayal of Dimitrie Sturdza Miclăușanu, the halt to the rapid independence of 1863 – 1864 through the intervention of Napoleon III, a hero of Europe, because he had managed to defeat the Tsar of Russia and the Romanian army’s deployment on the front during the war for independence 1977 – 1978 and the death of tens of thousands of Romanians on the front.

It is a discussion that shows that in this family, which has done quite a lot of harm to both Moldova and Romania, Dimitrie Sturdza, his son, Colonel Alexandru Sturdza and so on, an act beneficial for Romania has been delayed.

Of course, there have been researchers, like Mihaela Demian, who have tried to diminish Miclăușanu’s deed, but objectively speaking, and through the publication of the memoirs of Alexandru Ioan Cuza, who was an uncle of Dimitrie Sturdza Miclăușanu, nothing can erase from history, if one makes a real history, the act of malicious treason against all Romanians.

Prof. Valentin Ciorbea gave the presentation The union and development of the military fleet during the reign of Alexandru Ioan Cuza

During the reign of Prince Stephen the Great, one of the most beautiful ships was built, called Pânzarul Moldovenesc, with which he participated and helped him in the battles he fought at Chilia, and with which he went as far as Athos, where the prince, on his own money, sponsored, among other things, at the Zografu Monastery, a tower for ships. Finally, after the closure of the Ottoman control over the Black Sea, things got complicated because there was no possibility for Romanian corvette fleets to participate until much later. It was not until 1793-1796 that Nechiță Văcărescu asked Prince Alexandru Moruzi to intervene in Constantinople to obtain a haitisheriff to develop the fleet.

Indeed, on November 23, 1793, the ruler will issue the Hrisovul for the country’s ships that are to sail on the Danube. There is talk here of different categories – bolozane, etc.

Of course, not as many as the Romanians wanted were built, but nevertheless, the moment that goes towards modernization, on the creation of a military fleet, is found in the Organic Regulation in Article 184, which speaks of the service on the Danube line, which must be fulfilled with caices. It provided for 18 caiques for Wallachia, three each in the main ports on the Danube – Galati, Braila, Calarasi, Giurgiu, Izlaz and Calafat. The same was planned for Moldavia, although the border on the Danube was somewhat narrower. Some of these means of navigation on the Danube were taken over by the Russians during the Crimean War and most of them were certainly lost, worn out and obviously the question of their development was raised, which Alexandru Ioan Cuza did.

Cuza had a fulminating military career, in the sense that he obtained his ranks very quickly, but the fact that he held the rank of colonel imposed him in front of the commanders of regiments built or established in the Principality of Moldavia and in the Principality of Wallachia. In my opinion, Cuza had a unitary conception of the army. He even carried out a reform for the land army, he used the experience and a team of Frenchmen who came and helped to modernize the army and, within this, the fleet.

Cuza was interested in ensuring the freedom of navigation on the Danube, but at the same time to have a control for special situations and defense. Between April 1859 and September 4, 1859 is indeed the time of unification of the land troops, because, in addition to the joint exercises, it was a very great experience, with maneuvers even in the presence of Mr. Cuza, which made a connection, an understanding between the two armies, which were now in fact the United Principalities Army.

On the Danube there was a flotilla of several Moldavian and Muntenian ships, quite small and poorly equipped.

That is why the question of developing this military fleet has arisen. There were two points of view, I think, worth mentioning. Kogălniceanu was of the opinion that the fleet should be developed at the same time as the land army, while General George Adrian had a program for the development of the fleet, which would reach 16-20 gunboats with a fairly large number of personnel: 16 officers, 88 non-commissioned officers and sergeants and 500 troops.

Of course these figures could not be reached, but the idea was there. The problem that arose was that of unifying the flotilla, and rather quickly done.

On October 6, 1860, General Ioan Emanuel Florescu, Minister of War, proposed in a document the union of these two fleets, under the name of the Corps of the Flotilla, with the first base at Ismail. It was somewhere quite far from other important ports, Galati, Braila, Giurgiu.

After that he came back, and the report that he presented to Cuza would lead to another order of the ruler’s day, dated October 22, 1860, in which the request of Florescu, the Minister of War, is approved, whereby the fleets constitute a single corps, under the command of Colonel Steriade, of the Moldavian flotilla (former commander of the Moldavian flotilla) and Captain Constantin Petrescu, of Muntenia, who becomes his assistant.

There were only six gunboats, which were deployed, three each, in Chilia, Ismail, Galati, Braila, Giurgiu and Calafat, more for surveillance and to intervene if necessary.

Their mission was to control commercial ships, and if a health problem was reported, to isolate and take measures to prevent such diseases from spreading and becoming pandemic. Where did these soldiers come from? Quite simply. The officers were transferred from the rangers and infantry as the country did not yet have institutions to train them. The most suitable ones were those of the border guards. As for the soldiers, they were selected with training from the towns along the Danube, because they were used to the water, they knew how to handle a boat.

Cuza’s interest in the military fleet is also reflected in the budgets that this category of force received. In 1860, 360,000 lei, in 1863, 514,000 lei, and in 1866 he approved 2 million lei for equipment and personnel training.

The decision was made to send young men to school in France, and the best naval school in France was at Brest. That’s where the first officers were trained and they came with a great deal of experience, which they applied in the river fleet.

We mention Nicolae Dimitrescu Maican, Ioan Murgescu, who will become admiral and will make a famous march with the French ship Jean Bart, which helped him a lot in the command of ships in the Black Sea.

Ships were ordered to reinforce the fleet. In 1861, a merchant ship was bought in Galati, but in order to adapt it to the needs of the navy, it was sent to Vienna, to the Maier shipyard, where it was completely refitted and equipped with four cannons. She arrived on August 2, 1862 in Giurgiu, entered service, and General Savel Manu, who succeeded Florescu at the helm of the ministry, christened her Romania in the name of the prince. In this way, another ship, which Prince Cuza never got the chance to see, but because he was ousted, was commissioned in Vienna.

In 1867, a steam and sailing ship called Stefan cel Mare, with paddles, became a protocol ship. In 1863 there were 13 officers and 372 non-commissioned officers, sergeants and enlisted men and 5 civilian employees in the fleet. It is a rather large and very important figure.

These young men from the Navy trained with the ships that the Navy has, which is nothing more than artillery moving on the water. This was very important because in the War of Independence, it was sailors who used the artillery batteries of the guns, some of them taken from ships, and they responded at Calafat when the Turks bombarded Romanian soil for the first time. It is certainly a very important matter.

Cuza was also interested in the Merchant Navy. First of all, he took action on the information coming from Constantinople that many Greeks, who were the greatest navigators at that time, were using the Romanian flag, the Romanian flag, the Romanian flag without approval.

In 1864, when he made his second visit to Constantinople, this time he came to Cernavodă, he traveled by English train to Constanța and all historians believe that he thought that the Romanian principalities should have a port on the Black Sea. Of course, at that time it was not foreseen to be Constanta, but he asked the Parliament to think of such a place where to build a harbor. Jibrieni in southern Moldavia was chosen with the help of Charles Hadley, the great English engineer who solved the problem of the permanent navigable canal at Sulina.

A plan was made, but it never came together.

However, we can say that during the reign of Alexandru Ioan Cuza, a beautiful page was also written in terms of modernization of this category of armed forces.

Prof. Ioan Vlad said in his speech Where were the Transylvanian people when the union of the Principalities was realized that there was a special occasion in 1848-1849, when the Transylvanian Romanians, Avram Iancu and his army, who had achieved a military victory against the known adversaries of the Revolution, could have transformed this military victory into a political victory, could have declared himself head of state, could have transformed the War Council into a parliament, into a legislative forum of Transylvania.

Prof.univ.dr. Mihai Drecin – The Echo of the 1859 Union in Oradea and Beiuș

Of course, the Romanians in Transylvania knew the Romanian principalities very well since the Middle Ages because, economically speaking, exchanges were always made through the Carpathian passes, because the Carpathians were never a border between the Romanian countries, but rather a sieve through which people, ideas, material goods were sifted on either side of the Carpathians.

Certainly the event of January 1859 had an immediate echo in Transylvania. On this subject I have published a study in our annals, in volume 14, double issue 1-2 of 2023, from which I will select only one event. It is about Professor George Marchiș from the Greek-Catholic High School of Beiuș.

George Marchiș was a peasant’s child from Satul Mare County at that time. He attended secondary school in Baia Mare in the first half of the 19th century. He then attended the Greek-Catholic seminary in Oradea, the Academy of Theology at the University of Vienna, and finally, in 1859, thanks to the outstanding professional results obtained in this Baia Mare-Oradea-Vienna schooling, he was appointed by the Greek-Catholic bishop of Oradea, as a teacher at the Greek-Catholic High School in Beiuș, the famous high school founded in 1828 by the Greek-Catholic bishop of Oradea, one of the outstanding personalities of our national culture.

Here, George Marchiș will teach Latin, Greek, geography and history. What is interesting, but explicable, in history lessons, George Marchiș, like other teachers at Orthodox educational institutes in Transylvania, in addition to the history of the Habsburg Empire, in our case until 1867, and then in the history of Hungary, after dualism, Romanian teachers, priests or laymen, also taught the history of Romanians. Of course, with a certain risk that they declared to their pupils, who knew how to keep this secret within the walls of the Romanian schools, lest they fall into the hands of the Habsburg authorities, and after 1867, especially the Hungarian authorities, which were much tougher than the Habsburg authorities.

George Marchiș, as a student and then as a young teacher at the Greek-Catholic High School in Beiuș, corresponded with Romanian newspapers in Transylvania, for example with the Gazeta Transilvaniei from Beiuș, then with the magazines Sionul and Anvonul, published in Oradea by the Greek-Catholic Episcopate. George Marchiș writes, under the impulse of the happy event across the Carpathian Mountains, a national poem which he sends to the newspaper Naționalul in Bucharest, together with a letter in which he expresses his joy at the realization of the Union of the Romanian Principalities. The poem was entitled Voice from across the Carpathians.

Unfortunately, both the poem and the letter never reach their destination. The Habsburg guards intercept the letter and the authorities force the Greek-Catholic Diocese of Oradea to take action against the young professor George Marchiș. He will be summoned to Oradea and reprimanded, but it is clear from the documents preserved that his dojeana was more paternal than political.

It is true that the diocese has to dismiss him as a teacher at the Greek-Catholic High School in Beiuș, but the diocese will carefully place him in the coming years as a parish priest in a number of Greek-Catholic parishes in Sălaj and Sătmar. Little by little, after the event is forgotten, he will be reintegrated among the first-rate counselors of the Greek-Catholic Diocese of Oradea.

In my study, published in our Annals, issue 1-2, 2022, I have presented other moments from which the special echo of the “small union” among the Romanians of Transylvania emerges – first of all at the level of the upper elite of our nation, but through it, through teachers, professors, priests, the event penetrated the consciousness of the common man, of the minor village elites, but also at the level of the peasants, which was a step towards the consolidation of modern national consciousness among the Transylvanian Romanians.

Romanians have a long naval tradition.